1. Liability of managers, directors, members and legal agents

1.1. Introduction

The Tax Liability arises, at first, from the difference, in Brazilian system, between Direct Taxpayer and Indirect Taxpayer.

In fact, the National Tax Code (CTN) defines the Direct Taxpayer as the taxpayer personally and directly related to the situations giving room to the taxable even, while, on the other side, the Indirect Taxpayer as the individual or company that, without any personal or direct relation to the taxable event, has the tax charged on them by legal provisions.

We should set the premise that the company is an entity with rights and duties that cannot be misunderstood for the ones of individuals or the ones of the companies that are members thereof. Thus, such rights and obligations are limited to the property of such company, as a way of avoiding property commingling and punishments to the individual regularly managing it.

In tax law, the National Tax Code (CTN) allows for, under certain and rigorous conditions, notwithstanding said debt is the company’s, the redirection of the charge to the individual, either a member, officer, director, manager or legal agent of the company.

Such conditions are showed by the combination of the following factors:

1) it is a company subject to delectus personae;

2) the company regularly or irregularly liquidated does not exist anymore;

3) it is not possible to require the compliance with the tax obligation by the direct taxpayer, the company; and

4) there is action or omission by the person in charge, i.e., the one who has management powers over the company, acting in excess of authority, breaks the law or the articles of incorporation/organization, for example, spending the company’s property to their own benefit, not complying with rights and obligations before the company, etc.

There are discussions on the third-party liability being secondary or joint and several. The role of such difference is in the fact that, since the the liability between the company and the individual indirect taxpayers is deemed as joint and several, the tax entity can direct its charge, at first, to any one of them. On the other hand, since it is deemed as secondary, the tax entity can, at first, charge the debt to the company and, in case of possible success, direct the charge to the individual indirect taxpayers.

Brazilian courts, most of the time, treat the liability as secondary. However, it needs to be said that there are decisions that qualify the third-party liability as joint and several, i.e., they put the principal debtor – the company – and the indirect taxpayer at the same level, with the choice of which one of them should be charged for the performed obligation up to the creditor.

The difference carried out by the precedents, in order to treat the liability as being secondary or joint and several, is intrinsically related to situations in which the irregular dissolution of the company is showed, i.e., when the company stops working in its tax domicile without the duly information to the relevant bodies.

In any case, either secondary or joint and several, the third-party liability shall always depend on a commission or omission by the indirect taxpayer, i.e., the performance of an action for which they did not have powers or that represents a breach of the laws, the articles of incorporation or organization, in addition to the company’s irregular dissolution mentioned above.

On this aspect, it is important to highlight that, although the nonpayment of taxes can be superficially seen as a way of not complying with the tax laws, there is a firm understanding of such situation not being reason, sufficient in itself, to lead to tax charge. It is so provided in the precedent of the Superior Court of Justice no. 430:

“Precedent 430/STJ: The noncompliance with the tax obligation does not generate, in itself, the joint and several liability of the managing member”.

Then, the liability can only be characterized if, together with the noncompliance with the obligation, the indirect taxpayer has been proved to intend to perform actions against the law, the articles of incorporation or organization.

We can also recall the intention to perform an action against the laws or the articles of incorporation or organization must be proved by the tax authority through robust and sufficient evidences.

In addition, other characteristic inherent to the liability herein is: to be liable, the third party needs to have management powers, i.e., they must be a qualified third party, who is liable for debts incurred during its office, either they are or not in it, at the time of the charge.

Thus, a certain manager cannot be liable for taxable events that took place before their management. The reason for this, as we said, is that the liability by the manager can only be admitted in the cases in which they worked in excess of authority, braking the laws or the articles of incorporation, at the moment or period of their work before the company.

We shall now briefly analyze the liability of individuals in cases in which the company hypothetically stops operating, either for irregular dissolution or bankruptcy, since those are very common situations and they always lead to concerns by the managers.

1.2. Irregular dissolution of the company

The irregular dissolution of the company is set, as we mentioned above, when the company stops working in its domicile, without the duly information to the relevant bodies. This is what is provided in the Precedent 435 of the Superior Court of Justice, on this subject:

“An irregularly dissolved company shall be deemed as the one that stops working in its tax domicile, without the information to the relevant bodies, giving room to the redirection of the tax foreclosure to the managing member. (Precedent 435, FIRST SECTION, decision 14/04/2010, DJe 13/05/2010)”

Regarding this point, it is important to mention two Themes that were judged by the STJ about irregular dissolution and the imputation of tax liability to partners and non-partners of the company.

For Theme 962/STJ (REsps nºs. 1377019/SP, 1776138/RJ, 1787156/RS), the following thesis was established:

“The redirection of tax foreclosure, when based on the irregular dissolution of the executed legal entity or the presumption of its occurrence, cannot be authorized against the partner or non-partner who, although exercising management powers at the time of the taxable event, did not engage in acts with excess of powers or violation of the law, the articles of incorporation, or the bylaws, and who regularly withdrew from the company and did not cause its subsequent irregular dissolution, according to art. 135, III, of the CTN (National Tax Code).”

As for Theme 981/STJ (REsp nºs. 164533/SP, 1643944/SP, 1645281/SP), the following thesis was established:

“The redirection of tax foreclosure, when based on the irregular dissolution of the executed legal entity or the presumption of its occurrence, can be authorized against the partner or non-partner, with management powers on the date when the irregular dissolution is configured or presumed, even if they did not exercise management powers when the taxable event of the unpaid tax occurred, according to art. 135, III, of the CTN.”

Regarding Theme 962/STJ, the focus is on the liability of the partner or non-partner with management powers at the time of the occurrence of the unpaid taxable event. As for Theme 981/STJ, the focus is on the liability of the partner or non-partner with management powers at the time when the irregular dissolution was configured, regardless of the actual exercise of management at the time of the occurrence of the unpaid taxable event.

Thus, the conclusion of the STJ regarding Theme 962 is that the managing partner cannot be held liable although exercising management powers at the time of the taxable event, as long as they did not engage in acts with excess of powers or violation of the law, the articles of incorporation, or the bylaws, and regularly withdrew from the company without causing its subsequent irregular dissolution.

For Theme 981, the STJ concluded that tax liability may fall on the partner or non-partner, with management powers on the date when the irregular dissolution is configured or presumed, even if they did not exercise management powers when the taxable event of the unpaid tax occurred.

The interpretation of both themes is that they are complementary, as for the STJ, the conditions of liability or not, in the tax sphere, are:

a) No occurrence of acts with excess of power or violation of the law: evidence that the partner or non-partner engaged in acts with excess of powers or violation of the law, the articles of incorporation, or the bylaws – if there is no evidence of harmful acts, there is no basis for imputing liability;

b) Regular withdrawal from the company: The partner or non-partner who proves their regular withdrawal from the company, without contributing to the irregular dissolution, cannot be held liable, regardless of whether they exercised management powers at the time of the taxable event of the debt, and;

c) Remaining in management during the irregular dissolution: The partner or non-partner who remained in the company as an administrator or partner at the time of the irregular dissolution will be held liable, even if they did not exercise management powers on the date when the taxable event of the unpaid tax occurred. What matters is their presence in management during the irregular dissolution.

It is important to mention that the STJ is much stricter in situations where the irregular dissolution of the company is configured, as the discussed themes (981 and 962) penalize any administrator at the time of the dissolution, even if they were not in the company at the time of the occurrence of the taxable event. This is because irregular dissolution is repudiated by the jurisprudence and the legal system, being equated to a true tax fraud.

We should note a very reasonable reading of the precedent contents is that, in order to the irregular dissolution of the company to be characterized, there is no need for the company to effectively stop working; it only needs to change its address without the due information to the relevant bodies, such as the Federal Revenue Service, the State Finance Bureau, the Local Government where it is enrolled, etc.

Another fundamental point to which we call attention is the evidence in the records that the company was irregularly dissolved, with some decisions by the STJ, it shows the simple certification by the marshal in the tax foreclosure procedure saying they did not find or the company did not exist at the place for summons, would be enough to set the irregular dissolution of the company and authorize the redirection of the tax foreclosure to the manager:

“TAX. CIVIL PROCEDURE. TAX ENFORCEMENT. REDIRECTION. POSSIBILITY. INDICATIONS OF IRREGULAR DISSOLUTION. CERTIFICATION BY COURT OFFICER ATTESTING THAT THE COMPANY DOES NOT OPERATE AT THE ADDRESSES LISTED IN THE COMMERCIAL REGISTRY. SUMMARY N. 435/STJ. CONCLUSION OF THE LOWER COURT. REVIEW. IMPOSSIBILITY. SUMMARY N. 7/STJ. 1. The irregular dissolution of the debtor legal entity, verified through a certificate from the court officer attesting the closure of activities at the reported address, is a sufficient cause for redirecting the tax enforcement against the managing partner. Interpretation of Summary n. 435 of the STJ (AgInt in AREsp n. 1.832.978/PR, rapporteur Minister Gurgel de Faria, First Panel, judged on 09/26/2022, DJe of 10/03/2022). 2. It is not possible to overturn a decision that presumed the irregular dissolution of the company because the company does not operate at the address listed in the Commercial Registry. At this point, changing the presumption of irregular dissolution would require a re-examination of factual and evidentiary matters, which is not allowed due to the obstacle of Summary n. 7 of the STJ. Internal appeal denied.

(STJ – AgInt in AREsp: 2101929 RJ 2022/0098016-2, Rapporteur: Minister HUMBERTO MARTINS, Date of Judgment: 04/17/2023, T2 – SECOND PANEL, Date of Publication: DJe 04/19/2023)”

“CIVIL PROCEDURE AND TAX. PRE-QUESTIONING. ABSENCE. TAX ENFORCEMENT. IRREGULAR DISSOLUTION. REDIRECTION. POSSIBILITY. RE-EXAMINATION OF FACTS AND EVIDENCE. IMPRACTICABILITY. VIOLATED LEGAL PROVISION. INDICATION. NON-EXISTENCE. 1. There is a manifest absence of pre-questioning, attracting the application of Summary 211 of the STJ, when the lower court does not issue a value judgment on the thesis related to the allegedly violated legal provision, even after the filing of a motion for clarification, making it impossible to admit the fictitious pre-questioning introduced by art. 1,025 of the CPC/2015 if the party does not argue in the special appeal the violation of art. 1,022 of the CPC/2015 regarding the alleged omission. 2. The irregular dissolution of the debtor legal entity, verified through a certificate from the court officer attesting the closure of activities at the reported address, is a sufficient cause for redirecting the tax enforcement against the managing partner. Interpretation of Summary 435 of the STJ. 3. In cases where the special appeal faces the obstacle of Summary 7 of the STJ, as the verification of the non-existence of irregular dissolution of the business entity depends on the examination of evidence, an inappropriate measure in a special appeal. 4. The jurisprudence of this Superior Court is firm in the sense that the lack of clear and precise indication of the allegedly violated federal law provision implies a deficiency in the reasoning of the special appeal (Summary 284 of the STF). 5. Internal appeal denied.

(STJ – AgInt in REsp: 1719320 PB 2018/0011523-6, Date of Judgment: 06/27/2022, T1 – FIRST PANEL, Date of Publication: DJe 07/01/2022 REVJUR vol. 539 p. 125)”

1.3. Tax foreclosure redirection

Once the tax nonpayment is verified, and after the needed procedures, the creditor can extract the certificate of overdue tax liability – out-of-court cause to ground the filing of a tax foreclosure suit, instrument that can require the debtor to meet their obligation.

When there is no property that can undergo expropriation by the creditor, to pay the debt, and in case of the hypothesis provided for in tax laws, i.e., the performance of actions against the law, the articles of incorporation or in excess of authority, in addition to the irregular dissolution of the company, the judgment creditor can claim, before the judge, the redirection of the executive claim, in order to enforce the rule on third-party charging provided for in the articles above, by the CTN (National Tax Code).

This refers to the possibility that, during the tax enforcement directed at the corporate taxpayer, the assets of individuals who were originally not part of the enforcement’s passive subject can be reached, due to having committed acts with excess of powers, violation of the law, or the constitutive acts.

It is emphasized that “The mere non-payment of the tax does not, by itself, even theoretically, constitute a circumstance that entails the subsidiary liability of the partner, as provided for in art. 135 of the CTN (National Tax Code). It is essential, for this purpose, that they have acted with excess of powers or violation of the law, the social contract, or the company’s statute.”1

Regarding this aspect, the national precedents has always understand the creditor, in case of no property found, cannot simply request the redirection of the tax foreclosure to the indirect taxpayer. They must, before it, prove the hypothesis provided for in the laws as authorizing the individual liability.

Such situation, nonetheless, is not fully admitted when, although the tax foreclosure is filed only against the company, the name of the member is in the CDA (overdue liabilities certificate). In such hypothesis, the indirect taxpayer should prove they did not perform any continuing crime, excess of authority or violation to the articles of incorporation.

In such aspect, the unduly liable individual shall use procedural means needed to their defense, as, according to what we affirm herein, except for the hypothesis of irregular dissolution, which also depend on evidences – certificate by the marshal proving the company does not work at the place in its registry before public bodies anymore, for example – the tax foreclosure redirection is not automatic.

Although there is no express provision regarding the deadline for redirecting tax enforcement against directors, the five-year period provided for in Article 174 of the National Tax Code (CTN), used for filing tax enforcement after the definitive constitution of the tax credit, is considered applicable to the individuals mentioned in Article 135 of the CTN (National Tax Code).

Regarding the starting point of this period, it is generally the date of the service order on the taxpayer company in the tax enforcement. However, in cases where the fraudulent act is committed after the service on the company in the enforcement proceeding, the Superior Court of Justice (STJ) stated that “it is the date of the unequivocal act indicating the intent to render the satisfaction of the tax credit already under executive collection promoted against the taxpayer company unfeasible, to be demonstrated by the Tax Authority.”2

Although the Superior Court has clarified the temporal milestones, there are still uncertainties about what constitutes an “unequivocal act” that prevents the satisfaction of the credit by the Public Treasury.

1 Special Appeal nº 1101728/SP, Theme 97, Superior Court Of Justice – STJ.

2 Special Appeal Nº 1.201.993 – SP (2010/0127595-2)

1.4. Bankruptcy

Technically, bankruptcy is a legal and procedural judicial regime that, through a judgment, aims at the collective foreclosure of property of the debtor that cannot pay their debts. In such regime, the creditors seek, through the divisions of the property owned by the one undergoing bankruptcy, a way to pay the debts, according to certain rules set by law.

With the in-court adjudication of bankruptcy, the estate is formed – a true universality of rights – that starts to be liable for the debt in lieu of the company originally being charged.

Although one of the basic principles of the bankruptcy proceeding is, through the start of a bankruptcy case, assuring equitable conditions between creditors with the same nature, we need to recognize the laws in force provide for the preference of some credits before others, with such distinction based on public interest.

Thus, tax liabilities are privileged, as they must be payed in preference to others, except for credits arising from labor law or work accident and credits with collaterals at the limit of the value of the encumbered property.

We should, however, consider the tax credit is not included in the bankruptcy case and it is subject to allowance, so as the tax foreclosure pends independently of bankruptcy and its adjudication does not interrupt the tax foreclosure, as per the understanding of our courts.

On such aspect, it is important to mention the tax foreclosure, at first, continues against the estate. If, at the end, the property in the estate are not enough to pay the tax debts of the former company, its officers, members, agents and managers are not automatically liable, except if the hypothesis herein are verified.

Thus, without the characterization of the irregular dissolution of the company, its closing due to the adjudication of bankruptcy does not automatically generate the liability of the members, officers, managers and agents of the company, except the tax authority shows the performance of actions against the law, the articles of incorporation or in excess of authority.

1.5 Changes Introduced by Complementary Law No. 214/2025

In early January 2025, the Complementary Law No. 214 of 2025 was enacted, establishing the new consumption taxes resulting from the Tax Reform, namely: the Tax on Goods and Services (IBS), the Social Contribution on Goods and Services (CBS), and the Selective Tax (IS).

In addition to regulating these taxes, the Complementary Law also introduced specific provisions regarding third-party liability. However, it explicitly stipulates that the provisions of the National Tax Code (CTN), as commented on above, are not superseded by the enactment of this new law.

Generally speaking, the Supplementary Law innovates by expressly listing a set of actions that may give rise to joint and several liability of third parties. Meanwhile, Article 124, subsections I and II, also of the National Tax Code, in a separate chapter, provide that persons with a common interest in the situation that constitutes the taxable event, as well as persons expressly designated by law, are jointly and severally liable.

As a side note, Article 128 of the CTN provides that a third-party liable person must be directly connected to the taxable event giving rise to the obligation. Meanwhile, Article 124, items I and II, in a separate chapter of the CTN, establishes that individuals or legal entities with a common interest in the situation that constitutes the taxable event, as well as those expressly designated by law, are jointly and severally liable.

It can be observed that the CTN does not confuse third-party liability with the concept of joint and several liability. This is because the latter is not a form of selecting a liable taxpayer but rather a plurality of people with a common interest in the situation or by virtue of law. Therefore, these provisions must be interpreted together when dealing with third-party liability on a joint and several basis.

“The provision under Article 124, II, which states that ‘persons expressly designated by law’ are jointly and severally liable, does not authorize the legislator to create new cases of tax liability without observing the requirements set forth in Article 128 of the CTN.”

(Excerpt from the leading opinion of Justice Ellen Gracie in RE 562.276, in 2010)

For this reason, there may be considerable confusion in interpreting Complementary Law No. 214/2025, as it tends to treat distinct legal concepts as if they were one and the same.

Specifically, items I, II, and VI of the new law impose liability on individuals or legal entities that participate, under any title, in transactions not supported by proper tax documentation. Item IV imposes liability on those who develop or supply software designed to circumvent tax legislation. Finally, item V addresses those who conceal the occurrence or value of a transaction or who abuse the legal personality to evade tax obligations.

The logic adopted by the legislator may be summarized as follows: any party participating in such conduct is deemed to have contributed to the harm caused to the public treasury and may therefore be held liable for the non-payment of taxes.

By providing these provisions, the tax authorities effectively compel all parties involved in a transaction to monitor one another’s compliance with documentation and legal standards, as a means of avoiding personal liability.

The implementation of this joint and several liability framework will undoubtedly pose new challenges to entities throughout the production and supply chain, particularly with regard to the need for operational adjustments and more stringent control over commercial transactions.

Although the enforcement of tax obligations remains within the exclusive purview of the tax authorities, the imposition of joint and several liability will require companies and individuals to play a more active role in ensuring the tax compliance of their commercial partners.

2. Phases in which the tax and criminal tax liability can occur

As already highlighted in the chapter above, Brazilian tax law, like in many other countries, considered different hypothesis in which the liability for the payment of the unmatured (e.g. tax substitution) or matured (e.g. personal and joint and several liability) tax can be given to a taxpayer different from the one liable for the practice of the taxable event.

Thus, we shall now approach the particularities inherent to the phases of charging the already assessed tax liability that can lead to tax liability of third parties who did not (forcefully) take part in the taxable event, such as members, officers, managers, etc.

It is important to highlight that the following chapter shall approach the characteristics of the in-court and our-of-court tax litigations in federal scope (federal taxes), as for state and local taxes, we need to meet the particularities of the laws of each of the 27 federal entities and of the more than 5,500 municipalities.

Anyway, although there can be particularities in the laws of each of the referred federal entities, both tax proceedings and the structure of said revenue entities follow a reason that allows us to talk in a general way, as follows.

2.1. Out-of-court Phase (IN RFB no. 1862, of December 27th, 2018 and Ordinance PGFN no. 948, of September 15th, 2017)

2.1.1. During the out-of-court proceeding

a. Tax Authority assesses if there is evidence of the taxpayer incurring in any hypothesis (refer to previous chapter) of the laws giving room to joint and several or personal liability of officers/managers/legal agents of the notify company.

It is important to highlight that third parties can be held liable not only within the scope of the violation and penalty arising from the noncompliance with the main and accessory tax obligations, but also when it comes to compensations carried out by the direct taxpayer and not confirmed/approved by the tax authority (refer to art. 8, of IN RFB no 1.862/2018).

b. In such case, the public agent shall make the subjects above liable, and there is room for (i) creating an incident of “Tax Claim for Criminal Purposes” (refer to the next chapter), which shall wait for the end of the out-of-court tax litigation, and/or (ii) start a supervision procedure (small-estate probate) or (tax provisional) restraint on property in case the encompassed ones are classified within the hypothesis in the laws.

b.1. The small-estate probate is an administrative procedure carried out by the Federal Tax Authority when the sum of the tax liability (federal taxes) of the taxpayer simultaneously exceeds 30% of its known property and BRL2,000,000.00. There is no provision for out-of-court defense, but it is possible to challenge the procedure in court, in case the Federal Tax Authority does not understand or surpasses the requirements in the laws.

b.2. the tax provisional measure, on its turn, is the procedure that can be carried out in the same phase (or even after the out-of-court phase) when the Federal Tax Authority identifies the deliberate practice of actions by the taxpayer towards making the immediate or future payment of tax liability difficult (e.g. lack of domicile, property dissipation, assumption of different debts, etc).

c. Returning to the discussion before the administrative scope, in case there is no agreement with the notification and liability by the Federal Tax Authority, independent defenses shall be presented both by the company and by the indirect taxpayers (individuals), who, at first, can use the same lawyer or law firm. The discussion out-of-court does not require the payment of costs to the public entity or guarantee over the debt through a deposit or other type of guarantee.

It is important to highlight that the indirect taxpayer can approach, in their out-of-court defense, not only the matter justifying their (personal and/or joint and several) tax charge but also the reasons for the requirement for such tax liability not being due.

The discussion on the sufficiency of the tax notification and the tax charge to third parties (officers, managers, etc.) shall be carried out in two instances, that is, in case of a decision not granted to the initially presented defenses, there is room for an appeal before the court of appeals, composed in an equal way by judges representing the Tax Authority and representing the Direct Taxpayers (equality body).

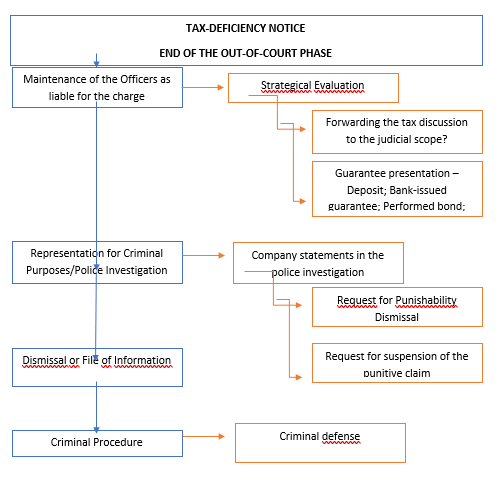

The end of the tax out-of-court litigation can be followed by three (03) severances, to wit:

(i) final decision granted to the integral extinction of the tax liability: In such case, the debt is extinct and, as a consequence, the liabilities over the companies and indirect taxpayers are also extinct. Any procedures for liability within the criminal scope and for the restraint/lien of property of the encompassed ones are also dismissed.

(ii) final decision granted only regarding the suspension of the joint and several/personal tax liability of officers (maintenance of the requirement for the company): In such case, the third-party indirect taxpayer (manager, officer, etc) shall have the tax charged, as it shall only be charged to the company, and it can discuss it in court. Possible property restraint/lien made on behalf of the indirect taxpayer are dismissed. Although improbable, it is possible that, in such hypothesis, the procedure for assessing the tax charge for a tax crime by the indirect taxpayer is maintained (refer to the next chapter).

(iii) final decision not granted, maintaining the joint and several/personal liability and the requirement for tax liability: In such case, both of them (company and indirect taxpayers) can bring to the courts the discussion ended out-of-courts either regarding the sufficiency of the tax charge and regarding the third-party tax liability (manager, officer, etc).

2.1.2. After the end of the out-of-court tax litigation and the in-court phase

2.1.2.1. Out-of-court, by the Federal Tax Authority of the Federal Revenue Service

After the dismissal of the out-of-court discussion with maintenance of the tax charge and the tax liability of third-parties, the liability shall be forwarded to be listed as overdue tax liability for later charge through a suit for tax foreclosure.

It is important to highlight, however, that in case the Tax Authority has not held third parties jointly and severally or personally liable during the out-of-court phase, it can fundamentally do it then (art. 15, IN RFB 1.862/2018), with those lately held liable having to file an appeal for discussion on the liability. Such appeal shall pend in an only instance and shall not suspend the procedures for tax charge and listing as overdue tax liability.

2.1.2.2. Out-of-court, by the Prosecution Office of the National Treasury (PARR)

Still before the forwarding of the liability for legal charge (tax foreclosure), the Prosecution Office of the National Treasury, in the specific case of suspicion on the irregular dissolution of the company, can start an Out-Of-Court Procedure for Tax Liability (“PARR” in order to assess the third-party liability (managers, officers, members, etc). Such procedure aims, in the greatest part, at seeking signs of irregular property dissipation by the ones responsible for the company about to undergo the execution of judgment.

The third parties held liable within the PARR shall be entitled to present a defense (within 15 days) and an appeal (within 10 days) in order to show the reasons for the insufficiency of the tax charge carried out by the Prosecution Office, and we shall highlight presenting such appeal does not interrupt the procedure for tax charge.

2.2. In-Court Phase

In the courts, the discussion on the sufficiency of the tax liability and the tax charge of third parties can be faced by the interested parties in two ways. Preventively/Proactively, from the initiative by them of advancing any procedure for in-court charge by the Government and filing the action for annulment of the tax liability. Or reactively, through the discussion within the tax foreclosure scope filed by the Government.

Both the forms presented above give room to the discussion of the defense matters related to the joint and several and/or personal liability of third parties and the sufficiency of the tax charge in itself, however, within the tax foreclosure scope, this discussion requires the guarantee of the charged value, which, in case it is not made through a deposit, insurance or bank-issued guarantee, shall be imposed by the National Treasury through property restraint of the assets of all the indirect taxpayers up to the limit of the charge.

The liability of third parties, such as members, managers, officers, etc, can also occur during the tax foreclosure (when it is not attributed and arises from the out-of-court discussion), when the National Treasury proves the irregular dissipation of the company, the commingling of the property of the company and its members, the existence of a business group in fact or any other factual/judicial situations that are signs of a possible fraud or property dissipation.

Regarding the hypothesis of inclusion of the members or officers, during the tax foreclosure, indicated above as an example, the indirect taxpayers must prove, throughout the suit (3 instances) the nonexistence of the situations provided for in the laws for liability, such as, (i) lack of irregular dissolution, (ii) irregular dissolution performed after the leave of the member, who could not intervene in the irregular dissolution after transfer of interest or shares (interpretation still not settled in the precedents), (iii) members or officers not having managing powers and, for this reason, not taking part in the possible decisions leading to the tax noncompliance, (iv) statute of limitations of the right to charge by the National Treasury, (v) regular dissolution of the company (proof of bankruptcy, making the member not liable), (vi) lack of business group in fact, among others.

3. Criminal Aspects

3.1 Introduction

There has always been a relation between the Tax and the Criminal Law and such theme is currently more relevant in Brazilian scenario due to the decision issued by the STF for judging the Appeal RHC 163,334, in which the STF decided the fact the direct taxpayer files and does not pay the ICMS over their own operations can be deemed a crime.

In the mentioned trial, the following thesis was established: “The taxpayer who repeatedly fails to remit ICMS (Value Added Tax on Sales and Services charged to the purchaser of goods or services – “State VAT”) to tax authorities with the intention to misappropriate falls under the criminal offense described in article 2, paragraph II, of Law No. 8.137/1990.”

The aforementioned thesis can be applied to both the ordinary method and the tax substitution method, according to the Superior Court of Justice’s Precedent nº 658/STJ.

Following this line of reasoning, the act of the taxpayer filing the ICMS tax return but not remitting their own ICMS to the Tax Administration would resemble the criminal offense of misappropriation, because by failing to remit the respective state tax, the taxpayer would be wrongfully appropriating a value passed on to the consumer that belongs to the State Treasury.

This is because, in practice, the formal State VAT ordinary taxpayer designated by the legislation, as the business entity engaged in sales and commercial activities, passes on the amount of the said state tax to the consumer, who, upon acquiring the product and/or service, pays a final price that includes the levied tax (State VAT).

Under this system, the amount of the state tax, destined to the public treasury, only passes through the accounting of the taxpayer (seller), who has the obligation to remit it to the State Tax Authority. The crime is considered to occur precisely when there is a failure in such remittance.

However, it is worth noting that failing to remit the levied tax is not enough to constitute the federal offense described in article 2, paragraph II, of Law No. 8.137/1990. Two additional requirements must be met: habitual non-remittance and the intention to misappropriate (i.e., the intention to appropriate unlawfully).

In fact, it was precisely on this aspect that Supreme Court Judge Luís Roberto Barroso established and emphasized in his vote in the trial of the leading case (RHC 163.334), the subtle difference between a potential debtor of ICMS, who is unable to bear the expenses of the state tax due to specific financial difficulties at a given moment; and a taxpayer who intentionally and knowingly fails to pay an amount filed in tax return to the State, using the undue subterfuge of artificially reducing the selling price of their goods and/or services, which implies engaging in unfair market competition.

In order to differentiate between one conduct and the other, the analysis of “potentiality vs. habituality” is one of the relevant criteria to be observed in order to determine if the crime actually took place.

In this regard, Judge Barroso’s vote addressed all the criteria that, together or separately, depending on each specific case, can be verified to identify the habitual conduct of a taxpayer indebted to ICMS, thus characterizing the crime of misappropriation. Let us see:

“It is necessary, therefore, to establish that the debtor’s non-compliance is repeated, systematic, and habitual, a true business model of the entrepreneur, whether for illicit enrichment, harming competition, or financing their own activities. This is an inherent element of the criminal fact that necessarily has to be identified by the judge in each specific case. In addition to the conduct of repeated non-compliance, consideration must also be given to the history of tax payments by the agent, despite specific episodes of non-payment, justified by specific factors.”, stated the Supreme Court judge.

In other words, the ICMS tax evasion cannot be a mere isolated incident but rather its repetition in different periods over time, revealing an illegal business model structured to engage in unfair competition and enrich the entrepreneur at the expense of the deliberate non-payment of state tax.

Furthermore, the intention to misappropriate must be established during the criminal proceedings (evidentiary stage) based on objective factual circumstances, such as “prolonged non-compliance without attempts to regularize the debts, selling products below cost, creating obstacles to inspection, using “straw men” in the corporate structure, irregular closure of activities, the amount of debts entered into active debt exceeding the paid-up share capital, etc. These circumstances are merely illustrative and must be compared with the existing evidence in the specific case to ascertain the subjective element of the offense.”

Therefore, for the characterization of the aforementioned crime, the company must engage in habitual non-payment of the tax, revealing a business model that considers the non-payment of ICMS as an important factor for the success of their enterprise.

Given that managing partners, as business owners and taxpayers of the state tax, may become defendants in legal proceedings involving the accusation of the criminal offense described in article 2, paragraph II, of Law No. 8.137/1990, it is advisable to seek adequate and constant legal assistance in order to mitigate potential criminal risks inherent to the daily operations of the company.

3.2. On Tax Crimes – Articles 1 and 2 of the Act no. 8,137/90

The more common Tax Crimes are provided for in articles 1 and 2 of the act 8,137/1990, and they basically approach the nonpayment/reduction in the payment of taxes and embezzlement, that is, retaining of a certain third value destined to any taxes and not paying them to the tax authority.

As a rule, due to what is set forth by the tax laws, the joint and several liability of an individual takes place in specific cases, to those who have a common interest on the situation giving room to the taxable event, and the secondary one to those who are personally liable for the credits corresponding to the tax obligations arising from the actions performed in excess of authority or violation of law, articles of incorporation or bylaws.

In other words, in order for the criminal liability of managers, members, directors, officers, etc. to take place, there is the need for the joint practice by those so as to lead to the taxable event under the tax point of view, and, in addition, there must be an willful act, such people must act willfully and intentionally, that is, as a rule, the one liable must be the one who gives room to the result.

In case of starting of an Investigation to assess the crime, there shall be the risk for the individuals to be investigated at first, and, in case the intention, the action or the omission are verified, there shall be the risk of a possible defense before a criminal procedure.

Of course, there is a number of defense elements that can be approached and proof documents that can help the criminal defense.

The current situation is a trend for more room to include individuals as liable for taxes and, as a consequence, for the criminal aspect.

There are two kinds of basic Liability, to wit: (i) through a suit, such as determining nonpayment of taxes; and (ii) through omission, not doing something that should be done, such as a specific obligation to checking the accounts. For this reason, legal assistance is needed.

3.2.1. We developed a hypothetical situation to facilitate understanding, as follows:

Let us hypothetically imagine that a company undergoes a tax notification for nonpayment of taxes or for the undue tax payment, and officers are included in the liability;

In case a decision is granted to the direct taxpayer, there is no room to consider liability under criminal aspects, as the tax in itself was dismissed by the decision.

However, in case a decision is not granted to the company and the others, the tax is definitively set and criminal severance can occur. Thus, the proper legal consultancy is very important to support the company still under the tax aspects, moreover for the fact that such liability can be dismissed still out-of-court and always assessing it together with the criminal risks.

In the presence or lack of specific request by the inspection to assess a crime, possible crimes can be assessed due to the independence of the tax and criminal legal areas, either by the Special Tax Authority or the Prosecution Office, through information by ex-employees, etc.

Important aspects that must be considered are the assessment by a tax law firm on the possible classification as tax crime, and the possible forwarding of the charge legal discussion.

In case the company choses to keep the discussion within the judicial scope, forms of guarantees for the charge must be evaluated. The company use to deposit the whole value of the charge or present a performed bond or bank-issued guarantee. Depending on the tax prosecution, the form of the guarantee must be strategically evaluated, also thinking on the possible criminal severance.

3.2.2. On the Dismissal of the Punishability and Suspension of the Punitive Claim for the crimes

The dismissal of the punishability is provided for in article 34 of act 9,249/95 and sets, in case the tax is paid, the direct taxpayer shall not be punished.

On the other hand, the suspension of punitive claim means the suspension of the right by the State of punishing the direct taxpayer, being such suspension conditioned to the charge in installments before the possible information filed by the Prosecution Office, a hypothesis provided for in article 68 of act 11,941/09.

An important aspect of the suspension of the punitive claim is that while the installments remain, there shall be no criminal statute of limitations. It means that in case the installments are not wholly complied with, the criminal procedure can be restarted.

3.2.3. Understanding of the Brazilian superior courts

We develop a precedents scenario on some points, as follows:

On the installments after the information is received, there is divergence of precedents, moreover for the fact that the laws determine the suspension of the punitive claim since the installment is performed before receiving the information. However, there are decisions granted to the direct taxpayers3.

The payment, as a rule, extinguishes the punishability at any time, before or after the information. Regarding it, Decision STJ HC 362.478/SP, DJe 20/09/2017.

There are still come details on the dismissal of Investigations while producing evidence in situations in which the direct taxpayer chose to forward the discussion to the courts and wholly deposited the value as a guarantee for the charge, in an understanding favorable to the direct taxpayer as above.

Thus, we conclude that there are arguments for defense and strategies that can be considered in the different phases of the out-of-court and in-court tax procedure, and, again, we should highlight the role played by the proper and constant legal assistance in order to mitigate the tax and criminal risks herein.

3.2.4 Criminal Implications in the Context of the Brazilian Tax Reform

Revisiting the context of the Tax Reform, it is known that there was a simplification and unification of consumption taxes, which were previously divided into ICMS, ISS, IPI, and the PIS and COFINS contributions, now replaced by the IBS, CBS, and IS.

Despite aiming to reduce distortions in the tax system, this simplification also brings new responsibilities for managers, who must pay attention to legislative changes and ensure compliance with the new requirements. This is because, even with the transition phase scheduled to begin in 2026, the introduction of this new system may increase the likelihood of errors due to a lack of knowledge or inadequacy to the new rules.

Therefore, it is recommended that managers, in particular, constantly update themselves on the reform to understand its impacts and establish tax compliance practices. They should also seek legal advice to mitigate the chances of criminal charges for violating tax legislation.

Laws related to it

1988 Federal Constitution;

Act 5172/66 – National Tax Code;

Act 8137/90 – Tax Crimes Act;

Act 9249 /95 and Act 9430/96 – On the Dismissal of the Punishability and Suspension of the Punitive Claim;

Act 10684/03 and Act 11941/09 – On the Dismissal of the Punishability and Suspension of the Punitive Claim;

Act 12382/11 – Representation for Criminal Purposes;

Authors: Rodrigo Minhoto and Carolline Polzella

Fleury, Coimbra & Rhomberg Advogados

Rua do Rocio, 350 – 10º andar – Vila Olímpia

BR-04552-000 São Paulo – SP

Tel +55 (11) 3294 1600

[email protected]

www.fcrlaw.com.br

Authors: Jorge Facure, Carlos Silva and Anna Julia Valasek

Gaia Silva Gaede Advogados

Av. Pres. Juscelino Kubitschek, 1830 – Condomínio do Edifício São Luiz

Torre II – 8º andar – Conjunto 82 – Itaim Bibi – – São Paulo, SP

Tel +55 (11) 3797 7400

[email protected]

www.gsga.com.br