2.a. Introduction

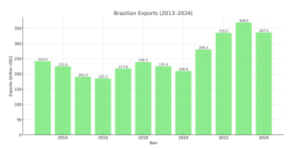

Brazil is one of the largest economies in the world, yet its share of global trade remains modest. In 2024, the country accounted for approximately 1,3 percent of global merchandise trade, considering both exports and imports by volume.

In recent years, Brazil has made progress in facilitating international trade through the digitalization of customs procedures, the signing of trade agreements, and regulatory simplification. Nonetheless, structural challenges persist, including a heavy tax burden, bureaucratic complexity, and logistical bottlenecks.

In 2024, exports and imports represented 33,3 percent of Brazil’s GDP, with exports accounting for 18,5 percent. This performance was mainly driven by the export of commodities such as oil, soybeans, iron ore, and beef.

Although there are over 20 million registered companies in Brazil, only 28.847 of them exported in 2024. This was a historical record, yet it still represents less than 0.15 percent of the total. The number of importing companies is estimated at around 50.000.

This context highlights both significant opportunities for growth and the need for strategic planning to operate efficiently in the Brazilian market.

2.b. Import Statistics

2.c. Export Statistics

2.2. Bureaucracy

Introduction

Foreign trade operations in Brazil are governed by a detailed regulatory framework. Starting import or export activities requires careful attention to specific steps and interaction with various government agencies. Failure to comply with the procedures may result in delays, fines, or cargo being held by customs.

In recent years, Brazil has made progress in modernizing its trade processes, especially through digitalization and better coordination between regulatory bodies. Still, the Brazilian regulatory environment demands planning, organization, and often the support of experienced professionals to ensure successful operations.

All international trade transactions must be registered in SISCOMEX (Integrated Foreign Trade System), an electronic platform managed by the Brazilian federal government. Through SISCOMEX, the Federal Revenue Service and other government agencies oversee, authorize, and monitor all stages of Brazil’s foreign trade operations. This process involves importers, exporters (or trading companies), customs brokers, freight forwarders, customs authorities, regulatory agencies, and the Central Bank.

Since 2023, the Brazilian government has been gradually implementing the DUIMP (Single Import Declaration), which is set to replace the current Import Declaration (DI) in various types of operations. The DUIMP consolidates customs, tax, commercial, and logistics data into a single digital document, improving efficiency, reducing clearance times, and standardizing import procedures. As of 2025, its use is already mandatory for certain special regimes, and the official schedule foresees the full migration of import records to this new format in the coming years.

Key Steps and Documentation

1. Licensing and Authorizations

Some products require prior licensing before entering or leaving the country. The approval depends on the nature of the goods and the responsible agency:

- Pharmaceutical and cosmetic products are regulated by ANVISA (National Health Surveillance Agency);

- Food, beverages, and goods of plant or animal origin require approval from MAPA (Ministry of Agriculture);

- Electrical and electronic equipment may require certification from INMETRO (National Institute of Metrology).

2. Customs Declarations

Each operation must be registered in SISCOMEX with detailed information, including the product’s tariff code (NCM), customs value, country of origin, destination, and applicable taxes.

3. Customs Clearance

This is the phase in which the Federal Revenue analyzes and authorizes the cargo release. Based on Brazil’s risk management system, shipments are assigned to a clearance channel:

- Green: automatic release with no inspection;

- Yellow: document verification only;

- Red: document and physical inspection;

- Gray: used in cases of suspected fraud, involving a thorough investigation.

4. Taxation

Several taxes apply to imports in Brazil:

- II – Import Tax (federal)

- IPI – Tax on Industrialized Products (federal)

- PIS/PASEP-Importação and COFINS-Importação – social contributions (federal)

- ICMS – Tax on the Circulation of Goods and Services (state-level)

Tax rates and calculation methods vary depending on the product type, country of origin, and destination state.

5. Logistics Documentation

In addition to customs declarations, the following documents are mandatory for clearance and international transport:

- Commercial Invoice

- Bill of Lading (BL) or Air Waybill (AWB)

- Packing List

- Certificate of Origin, when applicable

6. Inspections

Goods may be subject to inspection by agencies other than the Federal Revenue, depending on their nature. These inspections ensure compliance with health, safety, technical, and environmental standards.

Specialized Support

Due to the complexity of the system, it is highly recommended that companies, especially foreign ones, rely on experienced professionals, such as customs brokers and trade consultants. Their support helps avoid errors, minimize costs, and ensure compliance with all legal requirements.

This support is particularly important for companies entering the Brazilian market, helping them reduce risk, manage costs, and achieve operational predictability in their import and export activities.

2.2.a. Key Stakeholders in Foreign Trade

Importers and Exporters

To conduct foreign trade operations in Brazil, companies must obtain authorization from the Federal Revenue Service via Radar, which grants access to the SISCOMEX Single Portal.

Authorization is granted according to the company’s economic-financial capacity, with three main categories:

There are three main categories of Radar authorization:

- Limited – up to USD 50,000 per semester: Designed for small or new businesses, with simplified documentation requirements.

- Limited – up to USD 150.000 per semester: Allowed based on the company’s financial capacity; suitable for companies in the early stages of

internationalization. - Unlimited – above USD 150,000 per semester: Requires proof of stronger financial capacity and allows unrestricted operations.

Authorization Process

The authorization process is carried out electronically via the SISCOMEX Single Portal, based on an analysis of the company’s financial documentation and operational structure.

For newly established companies that require an unlimited Radar but do not have the necessary history to apply directly to the Federal Revenue, the company must present documents based on its operational period. In other words, an analysis of the company’s economic-financial capacity will be conducted based on the available information, considering the time of operation and its structure.

Timelines and Validity

The RADAR authorization is valid for 12 months but does not need to be renewed if there is activity within that period.

The process requires protocol submission in e-CAC and analysis by the Federal Revenue Service, which will define the type of RADAR the company will be granted.

Limit Review

Whenever a company plans to exceed the authorized limit, it must request a review of the limit before starting the process, to avoid having operations blocked by the Federal Revenue Service (RFB).

The process is carried out electronically on the SISCOMEX portal, based on an analysis of financial statements, revenue, structure, and financial capacity of the company.

This review is essential to adjust the limit to the company’s size and actual volume of operations, preventing blocks and delays in imports.

Key Documents Required for Limit Review

- Articles of incorporation and any amendments (including capital increases or integrations documented within the last 5 years).

- Signed trial balances and balance sheets.

- Bank statements and investments for the last 3 months (the most recent month must show the required minimum amount).

- Proof of expenses (electricity, rent, internet).

- Signed authorization request.

Key Considerations

- The Federal Revenue Service may deny the application if the documents do not demonstrate the required minimum financial capacity.

- Any changes to social capital must be registered.

Trading Companies

Trading companies play a key role in Brazilian foreign trade, offering comprehensive import and export solutions for businesses that choose not to operate directly in international trade.

In exports, companies commonly use a trading firm when they are not yet authorized under the Radar system. In this arrangement, the trading company conducts the operation in its own name, but the exporting company still benefits from the applicable tax incentives.

In imports, however, additional care is needed. The contracting company must be Radar-authorized even if a third party is handling the operation. There are two primary models for import operations involving trading firms:

- Import on behalf of third parties (Conta e Ordem de Terceiros): the trading company acts as an agent, importing goods using resources provided (or advanced) by the contracting company; the contracting party becomes the economic owner and bears the financial and fiscal responsibilities.

- Import “by Order” (Importação por Encomenda): the trading company purchases and imports the goods using its own resources, handles customs procedures, and then resells the goods to the predetermined contracting party; no advance payment by the contracting party is involved.

Both models offer logistical and fiscal advantages and are particularly useful for companies that want to outsource the management of trade operations and benefit from the experience of a trading firm.

For foreign companies, working with a local trading partner can be a strategic way to enter the Brazilian market with greater agility, compliance, and risk mitigation.

2.2.c. Customs Broker

A customs broker is a licensed professional authorized to represent importers or exporters before the Brazilian Federal Revenue Service in foreign trade operations. Their primary role is to register and manage import and export declarations in SISCOMEX, ensuring that all documentation complies with Brazilian customs regulations.

Beyond the operational aspects, customs brokers provide advisory services on tariff classification, risk assessment, licensing requirements, and tax calculation. They liaise directly with customs authorities, overseeing inspections, handling appeals, and assisting in cargo clearance.

During the clearance process, shipments go through a system of customs channels, which determines the level of inspection required. Goods are processed through customs clearance channels (Green, Yellow, Red, or Grey), each indicating a different level of inspection.

Channel selection can be random or based on factors such as the importer’s history, product type, country of origin, or any existing compliance issues.

The customs broker plays a critical role in minimizing risks, avoiding delays, and ensuring that the import or export process flows smoothly and in full compliance with Brazilian regulations.

2.2.d. Freight Forwarder

The freight forwarder is responsible for coordinating the international logistics of goods, managing the shipment from the country of origin to the final destination. This includes arranging freight services, consolidating cargo, issuing transport documents (such as bills of lading), and, when required, providing warehousing, insurance, and customs clearance services. In Brazil, the most commonly used transport modes are maritime, air, and road.

The logistics sector in Brazil has been undergoing digital transformation, with increasing use of integrated systems, real-time tracking, and more sustainable solutions such as route optimization and electric vehicles. The freight forwarder plays a strategic role in ensuring that goods are delivered accurately, cost-effectively, and on schedule.

2.2.e. Customs Authorities

The Brazilian Federal Revenue Service (Receita Federal do Brasil) is the agency responsible for customs control, tax collection, and anti-fraud enforcement in foreign trade operations. Its duties include document verification, physical inspection of cargo, application of penalties, and oversight of import-related taxes.

Unlike imports, exports from Brazil are largely tax-exempt. The government promotes international sales by waiving taxes such as IPI, PIS, COFINS, and ICMS, and by streamlining customs procedures.

Imports, on the other hand, are subject to a variety of taxes, including federal taxes (Import Duty – II, IPI, PIS, and COFINS), state-level ICMS, and additional charges such as the AFRMM (a freight surcharge on maritime transport) and other fees related to customs clearance. Due to the complexity of Brazil’s tax structure, proper customs and tax planning is essential for successful import operations.

In Brazil, customs authorities frequently engage in strikes, which can lead to delays in clearance procedures. These disruptions often result in additional storage costs for importers. As there is no effective way to prevent such situations, in certain cases companies may seek court orders (mandados de segurança) to secure the release of cargo during strike periods.

2.2.f. Regulatory Agencies and Other Government Entities

Depending on the nature of the goods, imports and exports in Brazil may require prior authorization from specific regulatory bodies. The main agencies include:

- ANVISA (Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency): Oversees medicines, cosmetics, food products, hygiene items, and medical equipment. Approval must be obtained before shipment.

- MAPA (Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply): Regulates goods of animal and plant origin. Also requires fumigation certification for wooden packaging.

- ANATEL (National Telecommunications Agency): Responsible for regulating telecommunications products and equipment.

- ANEEL (National Electric Energy Agency): Oversees equipment and projects related to the energy sector.

- INMETRO (National Institute of Metrology, Quality and Technology): Requires mandatory certification for various industrial and consumer products.

Other agencies may be involved depending on the type of product, such as:

- ANP (National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels)

- IBAMA (Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources)

These entities play a critical role in ensuring compliance with health, safety, environmental, and technical standards before goods can be legally traded across borders.

2.3 Logistics

2.3.a. Introduction

With a land area of approximately 8.5 million square kilometers, Brazil is the fifth-largest country in the world. This vast territory, combined with regional disparities in infrastructure, makes logistics one of the main challenges for doing business in the country.

While Brazil has made progress in port modernization, process digitalization and the expansion of logistics corridors, the national transport network still lacks integration, coverage and efficiency in many areas. The heavy reliance on road transport, instead of more competitive modes such as railways or waterways, increases logistics costs and limits the competitiveness of supply chains.

Efficient logistics coordination is therefore a strategic priority for any company planning to operate in Brazil. Proper management of transportation, storage and distribution is key to ensuring delivery timelines, controlling costs and maintaining service quality.

- Key Logistics Challenges in Brazil

Limited road infrastructure

Most cargo in Brazil is transported by road, but many highways are in poor condition. This increases transit times, operational costs and the risk of accidents. - Low multimodal integration

The lack of efficient connections between roads, railways, ports and airports affects transport flow and reduces the competitiveness of logistics routes. Intermodal transport remains underused. - Congested ports

Despite some localized improvements, many Brazilian ports face long waiting lines, shallow draft restrictions, low automation and outdated infrastructure. This impacts the cost and speed of import and export operations. - Complex urban logistics

In large cities, congestion, delivery restrictions and limited time windows increase the cost and complexity of last-mile logistics. - High logistics costs

Brazil has one of the highest logistics costs in the world relative to GDP. This is due to limited infrastructure, excessive bureaucracy, complex taxes, high fuel prices and tolls. - Bureaucracy and regulation

Excessive paperwork and overlapping regulations delay cargo processing and create uncertainty in operations. - Security risks

Cargo theft remains a major concern, especially in urban areas. This often requires companies to invest in tracking technology, insurance and, in some cases, armed escorts. - Adverse climate and geography

Heavy rains, flooding and other challenging conditions, particularly in the North and Central-West regions, can disrupt logistics routes and impact delivery performance.

2.3.b. Air Transport

2.3.b.i. Key Characteristics

Brazil’s air transport sector is considered safe and well-regulated. According to international rankings, Brazil ranks fifth among the safest countries to fly in, behind South Korea, the United States, Canada and Germany. Airport operations and infrastructure are managed by different entities, notably Infraero and, more recently, private consortia that have taken over the administration of several airports through public concession agreements.

The main international airports in Brazil are located in São Paulo (GRU), Rio de Janeiro (GIG) and Brasília (BSB). São Paulo is the country’s primary gateway for both international passengers and cargo. In 2024, Brazilian airports recorded around 118,3 million passengers, reflecting recovery and growth in the post-pandemic period.

For international travelers, customs clearance takes place at the first airport of entry. This can lead to long lines, especially at Guarulhos International Airport in São Paulo, which handles most long-haul international flights.

Regarding cargo transportation, import and export operations by air can be processed at various international airports across the country. Customs clearance is available at airports with appropriate infrastructure, such as Campinas (VCP), Curitiba (CWB), Recife (REC), Porto Alegre (POA), Manaus (MAO), Joinville (JOI) and Florianópolis (FLN), among others.

In recent years, the Swiss company Zurich Airports has taken over the management of several Brazilian airports, including Florianópolis International Airport (FLN), Vitória International Airport (VIX), Macaé Airport (MEA), and Natal International Airport (NAT). The company has been carrying out extensive modernization projects and actively working to attract new routes. These airports are expected to experience significant growth in the coming years.

It is important to note that foreign cargo aircraft are not allowed to operate domestic flights within Brazil. Therefore, the domestic distribution of imported goods or the collection of exports must be handled by licensed Brazilian carriers, such as LATAM Cargo, GOLLOG and Azul Cargo.

Air transport is commonly used for high-value goods, perishable items and time-sensitive shipments. The speed and security of this mode often justify its higher cost compared to sea or road transport.

2.3.b.ii. Major International Airports in Brazil

The five leading international airports in Brazil in terms of passenger volume, cargo handling and strategic relevance to foreign trade are:

- São Paulo/Guarulhos International Airport (GRU): The country ‘s main international gateway, handling the majority of long-haul flights and air cargo.

- Viracopos/Campinas International Airport (VCP): A key logistics hub for industrial imports and express cargo, especially in the São Paulo state region.

- Rio de Janeiro/Galeão International Airport (GIG): An important hub for southeastern Brazil, also serving regional trade with Mercosur countries.

- Brasília International Airport (BSB): A central hub connecting domestic and international routes, with strategic value for air cargo operations.

- Confins/Belo Horizonte International Airport (CNF): Emerging as a logistics center in the Southeast, with growing international connections.

2.3.c. Water Transportation

2.3.c.i. Key Characteristics

Below are the main Brazilian seaports, grouped by region, with a focus on those with the greatest strategic importance:

Southeast Region

- Port of Santos (SP): The largest port in Latin America, crucial for containerized cargo, agricultural exports and industrial goods.

- Port of Vitória (ES): Strong in the export of iron ore, steel, coffee and related products.

- Port of Rio de Janeiro (RJ): Important for general cargo, liquid bulk and regional supply operations.

South Region

- Port of Paranaguá (PR): Specializes in grains, soybean meal and frozen goods.

- Port of Rio Grande (RS): Handles fertilizers, grain exports and industrial cargo.

- Port of Itajaí (SC): One of Brazil’s top ports for exporting meat and manufactured products.

- Port of Itapoá (SC): Recognized for operational efficiency and modern infrastructure, with deep-water capacity and fast vessel turnaround.

- Port of Navegantes (SC): Strategically located with direct access to industrial hubs, strong in refrigerated cargo and container handling.

Northeast Region

- Port of Suape (PE): A modern port focused on fuel, chemicals and industrial operations.

- Port of Salvador (BA): Handles petrochemical, chemical and pulp cargo.

North Region

- Port of Manaus (AM): A vital logistics hub for the region, serving the Manaus Free Trade Zone. Handles industrial goods and electronics.

- Port of Belém (PA): Offers strategic access to northern Brazil and handles exports of minerals and grains.

Benefits and Challenges of Waterway Transport in Brazil

Benefits

- High capacity for moving large volumes of cargo.

- Lower transportation cost per ton over long distances.

- Direct access to international markets, supporting trade balance and export growth.

Challenges

- Need for modernization of port infrastructure, including dredging, automation and terminal expansion.

- Excessive bureaucracy and lengthy customs clearance processes, reducing efficiency and predictability.

- Congestion at land access points and delays in port hinterland areas. ● Limited intermodal integration, which hinders efficient cargo distribution to inland regions.

2.3.d. Road Transport

2.3.d.i. Characteristics

Road transport is the primary mode for moving cargo and passengers in Brazil, representing the largest share of the country’s logistics network. The national road system spans over 107,000 kilometers, with approximately 19,500 km operated under private concessions (with tolls) and 87,500 km under public management.

However, only about 43% of the roads are rated as being in good or excellent condition. The remainder suffers from structural deficiencies. The South and Southeast regions generally have better paving and signage, reflecting larger infrastructure investments over recent decades.

Benefits for Foreign Trade

- Operational flexibility: Allows door-to-door delivery, facilitating the movement of goods of various sizes, including to remote areas.

- High coverage: Reaches locations not served by railways or ports, enabling national distribution of imported goods and the flow of exports.

- Speed over short distances: For short and medium-haul routes, road transport is often faster than other logistics alternatives.

Challenges

- Uneven infrastructure: Poor road conditions increase transit times, vehicle wear, and the risk of accidents.

- High logistics costs: Fuel, tolls, and maintenance make road transport expensive, especially over long distances.

- Security risks: Cargo theft remains a concern, requiring investments in tracking systems, insurance, and armed escorts on certain routes.

2.3.e. Rail Transport

2.3.e.i. Characteristics

Brazil’s railway system holds significant potential but faces long-standing limitations in terms of its network coverage, modernization, and integration with other modes of transport. The existing rail infrastructure was originally developed to serve specific purposes, primarily the transportation of agricultural and mineral commodities, and remains concentrated in the Southeast, South, and Central-West regions. Despite years of limited public investment, concession agreements and public-private partnerships have driven efforts to expand and modernize the sector. Rail transport is expected to play a more prominent role in Brazil’s logistics matrix in the coming years.

Benefits for Foreign Trade

- High cargo capacity: Well-suited for transporting large volumes, particularly grains, minerals, fuels, and industrial inputs.

- Energy efficiency: Fuel consumption per ton transported is significantly lower than in road transport.

- Lower environmental impact: Reduced CO₂ and pollutant emissions, contributing to sustainability goals.

Challenges

- Outdated infrastructure: Much of the railway network requires upgrades, expansion, and better maintenance.

- Limited logistics integration: Weak connectivity between railways, ports, and highways hinders the efficiency of intermodal transport.

- Need for investment: Expanding the rail network depends on substantial public and private investment to enhance competitiveness and territorial coverage.

2.4. Import Cost Structure

Importing goods into Brazil involves a range of taxes and charges that directly affect the final cost of the product. Understanding these elements is essential for setting prices, assessing the feasibility of operations, and ensuring tax compliance. Errors in product classification or tax calculation can lead to penalties and financial losses.

Key cost components include:

- Import Duty (II)

- Excise Tax on Industrialized Products (IPI)

- State Value-Added Tax (ICMS)

- PIS and COFINS on imports

- AFRMM (Additional Freight Charge for Merchant Marine Renewal)

- Logistics and customs-related fees (such as storage, terminal handling charges, and customs brokerage)

The total tax burden depends on the product type, the destination state, the company’s tax profile, and the availability of incentives such as the Drawback regime or the Ex-Tarifário program. Coordination between tax, accounting, and logistics departments, along with reliable local expertise, is essential to reduce risks and optimize import costs.

2.4.a.i. Import Duty (II)

This is a federal tax levied on the entry of foreign goods into Brazil. It serves a regulatory function and aims to protect domestic industry. The applicable rates vary from 0% to

35%, depending on the product’s classification under the Mercosur Common Nomenclature (NCM), the type of good, and the country of origin.

For international shipments valued up to USD 3,000, such as online purchases, the rate may reach 60%. Non-commercial shipments between individuals valued up to USD 50 are exempt.

Import Duty does not generate tax credits. In 2024, the Brazilian government temporarily increased the rates for certain steel products as a trade defense measure.

2.4.a.ii. Tax on Industrialized Products (IPI)

IPI is a federal tax applied to industrialized products, both domestic and imported. For imports, it is charged upon customs clearance. Rates are defined by the TIPI (IPI Tax Rate Table) and vary widely depending on the type of product.

Companies under the Real Profit or Presumed Profit tax regimes may offset the IPI paid as a credit. Companies under the Simples Nacional regime are not entitled to such credit. Brazil’s 2025 Tax Reform provides for the gradual replacement of the IPI with the Selective Tax (IS), which will apply to products considered harmful to health or the environment. The transition is expected to be completed by 2033.

2.4.a.iii. PIS and COFINS on Imports

These are federal social contributions levied on the importation of goods and services. They represent a significant portion of the overall tax burden in foreign trade. Companies under the non-cumulative tax regime (Real Profit) may use the amounts paid as tax credits, including those related to freight, insurance, and other costs associated with their economic activity. Companies under the Presumed Profit regime are not entitled to this credit.

Since 2024, an additional temporary rate of 0,8% has been applied to COFINS on imports, in effect until 2028. Normative Instruction RFB No. 2,264/2025 also expanded the definition of inputs eligible for tax credits.

These contributions will be replaced by the CBS (Contribution on Goods and Services) between 2026 and 2027. Until then, the current rules remain in effect.

2.4.a.iv. ICMS (Tax on the Circulation of Goods and Services)

ICMS is a state tax applied to the circulation of goods, including imports. The rate ranges from 17% to 23%, depending on the destination state.

Some states, such as Santa Catarina and Espírito Santo, offer special import regimes that significantly reduce the overall tax burden.

Taxpaying companies may use the amount paid as a credit to offset against their sales. ICMS is one of the most impactful taxes in determining the final cost of imported goods.

Final Considerations and Recommendations

- Brazil has one of the most complex tax systems for import operations.

- The total tax burden varies depending on the type of product, the destination state, and the company’s tax regime.

- Engaging specialized advisory services is essential to avoid errors, reduce operational costs, and ensure full compliance.

- Closely monitoring ongoing tax reforms is critical to efficiently adapt corporate strategies and internal systems.

2.4.a.v. Brazilian Tax Reform

Constitutional Amendment No. 132/2023 introduces the most comprehensive reform of Brazil’s tax system in decades. The reform aims to simplify the taxation of consumption while promoting greater transparency, neutrality, and legal certainty for businesses. The main changes include:

- Replacement of five existing taxes (PIS, COFINS, IPI, ICMS, and ISS) with two new taxes: the Contribution on Goods and Services (CBS), under federal jurisdiction, and the Tax on Goods and Services (IBS), under state and municipal jurisdiction

- Creation of a Selective Tax (IS), applied to products considered harmful to health or the environment

- Gradual implementation of the new system between 2026 and 2033, with transitional periods and rate adjustments

- Progressive elimination of special regimes, tax benefits, and state-level incentives currently in effect

For foreign companies, it is essential to follow the implementation schedule, assess the impact on supply chains, and review operational and logistics models. The reform is expected to make the tax system more uniform and predictable, representing a potential improvement in Brazil’s overall business environment.

2.5 International Trade Incentives

2.5.a. Export Incentives

Brazilian exports continue to benefit from significant tax incentives, which remain stable and have been reinforced by the federal government. Exports are exempt from ICMS (Tax on the Circulation of Goods and Services) and IPI (Tax on Industrialized Products), which enhances the competitiveness of Brazilian goods in international markets. Depending on the company’s tax regime, exports may also be exempt from PIS (Social Integration Program) and COFINS (Contribution for the Financing of Social Security), further reducing associated costs.

Companies that use trading companies to carry out export operations remain eligible for the same tax benefits, which adds flexibility and efficiency to foreign trade transactions. Likewise, sales to Free Trade Zones (ZLCs), such as the Manaus Free Trade Zone, are exempt from taxes and treated as equivalent to export operations.

The Brazilian government continues to promote export-oriented policies, particularly in strategic sectors such as agribusiness, technology, energy, and manufacturing.

2.5.b. Import Incentives

Some Brazilian states, such as Espírito Santo, Santa Catarina, Pernambuco, and others, offer tax incentives for import activities aimed at attracting investment and promoting local economic development. These states provide reduced ICMS rates, which can significantly lower import costs and encourage the entry of strategic inputs to strengthen domestic production chains.

Companies planning to start or expand operations in Brazil should consider these regional incentives, especially when customs clearance is carried out at ports and airports located in these states. Such benefits can generate competitive advantages and reduce operational expenses.

At the federal level, complementary policies also promote the importation of inputs and capital goods through mechanisms such as the Ex-Tarifário regime, which contributes to increased productivity and innovation in the industrial sector.

2.6. Corruption

Corruption remains a relevant challenge within Brazil’s institutional environment. However, increased public exposure of cases and the proactive role of oversight agencies have driven important changes in business culture and strengthened transparency.

In foreign trade, corruption cases typically arise from procedural failures or inconsistencies during customs clearance. The adoption of digital systems such as SISCOMEX and RADAR has helped mitigate this risk by reducing the need for in-person interactions and improving the traceability of operations.

These automated platforms enhance government oversight, promote transparency, and make irregular practices more difficult.

For companies engaged in import and export activities, strict compliance with legal requirements, proper document management, and alignment with best compliance practices are the most effective measures to prevent corruption-related risks.

2.7. Common Mistakes in the Foreign Perspective on Brazil

2.7.a. Is Brazil a Cheap Country?

A common perception among international visitors is that Brazil is a cheap country, usually based on tourist experiences such as affordable meals or low-cost local services. However, this impression does not reflect the actual cost of operating a business in the country.

Although average wages in Brazil are lower than in Europe or North America, the tax burden and social security contributions significantly raise operational costs for companies. Inputs, components, and equipment may also be expensive, even when locally produced, due to factors such as limited production capacity, inadequate infrastructure, high logistics costs, and a complex tax system.

The steel industry clearly illustrates this reality: although Brazil is one of the largest steel producers in the world, domestic prices often exceed international levels. Therefore, operating in Brazil requires careful cost analysis to ensure financial sustainability.

2.7.b. Transportation and Mobility

Mobility in Brazil presents structural challenges. In many regions, especially in the North and remote areas, roads are poorly maintained and inadequately marked. Even in more developed states such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, certain stretches still suffer from deficient infrastructure.

Rail transport is limited and mainly dedicated to freight. Although modernization projects are underway, they do not yet provide a comprehensive solution. On the other hand, air transport is considered safe, widely used, and has undergone significant improvements, particularly through investments in connectivity and airport infrastructure across the North, Northeast, South, and Southeast regions.

2.7.c. Export Products and Challenges

Brazil is one of the world’s leading exporters of commodities such as beef, soybeans, coffee, and ethanol. The country also has a robust industrial base and companies with an international presence in strategic sectors, demonstrating its ability to compete in more sophisticated value chains.

Notable examples include Embraer, a global leader in regional aircraft manufacturing, and the national automotive industry. However, barriers such as a high tax burden, domestic logistics costs, exchange rate volatility, and a complex regulatory environment continue to limit the growth of higher value-added exports.

2.7.d. Product Pricing

Brazil’s tax system is characterized by the overlapping of federal, state, and municipal taxes, often applied cumulatively. This complexity directly impacts product pricing and can make certain items less competitive.

Foreign companies facing competitiveness challenges should consider a specialized tax analysis. In many cases, it is possible to optimize the tax structure and reduce operational costs. The Tax Reform (Constitutional Amendment No. 132/2023), which will be implemented between 2026 and 2033, aims to simplify the current system by replacing multiple taxes with a more uniform model.

2.7.e. Locations

While São Paulo is the country’s main economic and financial center, other regions also offer significant business opportunities. The South, Southeast, and Northeast host expanding industrial, technological, and logistics hubs, with the presence of major automakers and multinational companies.

When selecting a location, companies should consider factors such as infrastructure quality, availability of skilled labor, tax incentives, and operational costs. Many cities outside the Rio–São Paulo axis offer strategic and logistical advantages that may provide more efficient solutions for certain business models.

2.7.f. Country Size

Brazil covers an area of approximately 8.5 million square kilometers, making it about 200 times larger than Switzerland and nearly twice the size of the European Union. This vast territory presents significant logistical challenges, particularly for companies seeking nationwide coverage.

Business models based on multiple regional distribution centers—especially in the South, Southeast, and Northeast—tend to be more efficient. In addition, partnering with experienced logistics providers who understand local specificities and offer multimodal solutions is essential to mitigate risks and ensure operational efficiency.

2.7.g. Culture

Brazil’s cultural diversity is one of its most distinctive characteristics, resulting from the blend of Indigenous, African, European, and various immigrant populations. This richness is reflected in the country’s customs, cuisine, architecture, and ways of life, which vary significantly across regions.

The Northeast region preserves strong African cultural roots. The South is influenced by Italian and German immigration, with notable examples in cities such as Blumenau and Joinville. In the Southeast, São Paulo is home to large communities of Japanese, Italian, Arab, Korean, and Latin American immigrants, creating a dynamic and multicultural urban environment.

Foreign companies that embrace this diversity and operate with cultural sensitivity tend to achieve greater acceptance and success in the Brazilian market.

2.7.h. Language

Brazil is the only country in South America where Portuguese is the official language, with significant differences from European Portuguese. For institutional materials, it is recommended to use native Brazilian translators to ensure proper and natural communication.

English proficiency in Brazil remains low. Surveys by the British Council indicate that only around 5% of Brazilians have some knowledge of the language, rising to 10% among young adults aged 18–24, while just 1% of the population speaks English fluently.

2.7.i. The Brazilian Domestic Market

With approximately 213 million inhabitants, Brazil is one of the largest consumer markets in the world. Its GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP) was about USD 19,648 in 2024, below the global average of USD 27,291.

This means that while only a portion of the population has income levels comparable to European markets, in absolute terms this represents tens of millions of consumers. Therefore, it is a market that cannot be overlooked. In addition, Brazil’s overall market size and the expansion of its middle class present concrete opportunities for foreign companies, particularly in digital retail, education, healthcare, mobility, and technology.

2.8 Trade Agreements and International Integration

Brazil is a member of Mercosur, an economic bloc that also includes Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Bolivia. Through Mercosur, the country participates in trade agreements with a variety of partners, including the European Union (under negotiation), EFTA (which includes Switzerland), Israel, Egypt, India, and several Latin American nations.

These agreements include tariff reductions, trade facilitation measures, rules of origin, and technical cooperation. Depending on the product and its origin or destination, foreign companies may benefit from preferential tariffs when exporting to Brazil.

In addition, Brazil is a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and adheres to the principles of multilateral trade agreements. Companies must comply with relevant regulations, certifications, and specific sanitary and technical requirements as defined in each agreement or bilateral treaty.

Given the regulatory complexity and the specific features of Brazil’s trade agreements, international firms are strongly encouraged to engage with experienced local advisors. This support facilitates proper use of tariff benefits, ensures regulatory compliance, and enables strategic adaptation to Brazil’s international trade environment.

Author’s: Victor Albert Batista da Silva, Lucilene Aparecida Queiroz, Maria Eduarda Fernandes Hahn e Milane Brixi

Forvm Comércio Exterior Ltda

Rua Jaroslau Clemente Pesch, 34 Floresta, Joinville, Santa Catarina, Brasil Site:

Phone: +55 (47) 3433 0641

E-mail: [email protected]